- Home

- Lewis Carroll

Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense Page 2

Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense Read online

Page 2

Another group of poems, the Oxford satirical poems, have lost a good deal of their appeal since they are bound up with long-gone controversies of seething importance to members of those close-knit communities during Carroll’s, or Dodgson’s, long residence in college. Some still have enough play in them to entertain, such as “The New Belfry of Christ Church, Oxford”, which provoked him to witty revisions of King Lear and The Tempest and some syllogistic comedy. As ever, he writes with panache and variety so that even though the cause is long forgotten the wry humour survives.

Five fathoms square the Belfry frowns;

All its sides of timber made;

Painted all in greys and browns;

Nothing of it that will fade.

Christ Church may admire the change –

Oxford thinks it sad and strange.

Beauty’s dead! Let’s ring her knell.

Hark! now I hear them – ding-dong, bell.

(“Song and Chorus”)

That neat comma added to Ariel’s “ding dong bell”, so that it becomes “ding-dong, bell”, shifts the scale of mourning from a father lost, but unexpectedly equals it with “Beauty’s dead!”, the bell muffled in this raw new belfry. Instead of loss and fading, as in Ariel’s song in The Tempest, here the threat is permanent ugliness: “Nothing of it that will fade” instead of “Nothing of him that doth fade / But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange” (i, 2, 400-402). Christ Church, Dodgson here muses, is stuck with a permanent monstrosity without transformation. This present edition gives only the verses from these Oxford controversies but they have their full zest in their setting of prose argument and debate, too extensive for inclusion here.

The third and most famous group of his poems is addressed not only to a known but to an unknown readership. Alice’s Adventures Under Ground is still addressed to a known reader, the young Alice Liddell, and that first version remained unpublished for many years.4 But after that comes the publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1872), The Hunting of the Snark (1876), and much later, the two-volume novel Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893). In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Carroll’s skill as a parodist becomes part of a larger psychological adventure as Alice struggles to recall the pious verses with which she descended into Wonderland only to hear them emerge as exuberant violence, sometimes from her own mouth. In Through the Looking-Glass some nursery rhymes remain intact – “Humpty Dumpty”, “Tweedledum and Tweedledee”, “The Lion and the Unicorn” – while alongside them Carroll gives the full “Jabberwocky” and “The Walrus and the Carpenter”, to say nothing of Humpty Dumpty’s maddening song that ends with conjunctions, leaving the reader stranded on the brink of obscure crisis:

And he was very proud and stiff:

He said “I’d go and wake them if———”

I took a corkscrew from the shelf:

I went to wake them up myself.

And when I found the door was locked,

I pulled and pushed and kicked and knocked.

And when I found the door was shut,

I tried to turn the handle, but———

There was a long pause.

“Is that all?” Alice timidly asked.

“That’s all,” said Humpty Dumpty, “Good-bye.”

(Centenary Edition, 192)

If the joke there is emptiness, the White Knight’s song a little later is full: of feeling, of absent-mindedness, of Wordsworthian condescension and exasperated encounter. Its subject matter parodies Wordsworth’s poem “Resolution and Independence”, a prolonged account of a meeting between an insistent questioner and an old leech-gatherer, in which the questioner is depressed and alone. He is obscurely heartened by the old man’s wisdom, drawn out of him by indefatigable queries: “What occupation do you there pursue?” “How is it that you live, and what is it you do?” Carroll gets the mismatch between the questioner’s high and self-absorbed thoughts and the leech-gatherer’s own account with its hints for alms: Carroll wrote to his uncle Hassard Dodgson in 1872 that the poem had always amused him, “by the absurd way the poet goes on questioning the poor old leech-gatherer, making him tell his history over and over again, and never attending to what he says. Wordsworth ends with a moral – an example I have not followed” (Letters, i, 177). Carroll’s poem is in fact a reworking of an earlier poem of his own that had appeared anonymously in The Train in 1856. One of the marvellous turns in the Alice books is the way that such earlier poems are reinvented by embedding them in particular characters, or – as with “She’s All My Fancy Painted Him” – in a particular situation. That poem in the Comic Times (1855) grows menacing when set anew (and abbreviated) at the end of Alice in Wonderland.

His last two works of fiction, Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, with their constant miasmic shadings across different forms of reality and dream, accommodate an extraordinary variety of poems with no attempt to drive them through the narrative, even to the degree that occurs in the two Alice books. But the poems are generated out of the characters in the book and are appropriate to each one in particular rather than flowing straight from Lewis Carroll. These books, indeed, are full of buried treasure and the poems represent an arresting new phase in Carroll’s creativity, more sardonic, more extreme and more moving than his earlier parodies. Indeed, almost none of the poems in these late novels is parodic. At one extreme of feeling we have the idealised song of Sylvie and Bruno with its chorus:

For I think it is Love,

For I feel it is Love,

For I’m sure it is nothing but Love!

(“A Fairy-Duet”)

These stressful verses, urging love, are contrasted with vengefully logical poems such as “Peter and Paul”, where Peter is trapped by a loan never in fact given; or the Gardener’s Song that crops up again and again with new verses always structured by “He thought he saw” and “He looked again”: for example:

He thought he saw an Albatross

That fluttered round the lamp:

He looked again, and found it was

A Penny-Postage-Stamp.

“You’d best be getting home,” he said:

“The nights are very damp!”

Or:

He thought he saw a Garden-Door

That opened with a key:

He looked again and found it was

A Double Rule of Three:

“And all its mystery,” he said,

“Is clear as day to me!”

The Gardener’s Song marks the point where whimsy and grotesque become untranslatable, even indistinguishable. The delight and the exasperation felt by the listeners in the book (and probably by the reader) can’t be separated. The everyday and the exotic, postage-stamp and albatross, oscillate in these purest forms of nonsense. Carroll shifts speech-registers without remark while always respecting the demands of metre and rhyme: that calm provokes the sense of something uneasy, even unconscionable, that many readers experience even as they delight in the dexterity of the verse.

There was a further constituency of individual readers for whom he wrote his most occasional verse: the array of child-friends he gathered across the years, some of whom remained his friends into adulthood. The verses he wrote for these young girls (for all these poems were addressed to girl children or adolescents, sometimes as a family group) tended to be games in themselves, with hidden names and riddles. The ingenuity of the acrostics follows tight rules. Intimacy and bounds are both respected in these agile inventions. They vary from fond and simple compliments like this small poem addressed “To Miss Margaret Dymes” where the first letter of each line spells her name:

Maidens, if a maid you meet

Always free from pout and pet,

Ready smile and temper sweet,

Greet my little Margaret.

And if loved by all she be

Rightly, not a pampered pet,

&n

bsp; Easily you then may see

’Tis my little Margaret.

– to elaborate double acrostics, like the one addressed to Agnes and Emily Hughes, where each verse not only hides their names but is also a riddle (p. 294). Clearly, Carroll delighted in these codes and riddles as he delighted in the company of the girl children who were his friends: the fun and play was curbed and yet made more exhilarating by intricate rules. The inhibition of rhyme and the control of acrostic sorted well with his exquisite affection for the children – affection that knew its own bounds, and the necessity for those bounds. Very often these little poems occur in a letter, on the flyleaf of a book he is giving, or as a way of greeting or parting: they are presents, more personal and so more valuable than toys or trinkets, and clearly received as such by many of the girls who were given them and who kept them into adulthood. They are also teases, quite often apparently scolding as much as praising the child who is their inspiration. In the double acrostic poem below, each verse, after the first one, is a riddle (with the answer beside it) and the names of the little girls addressed provide the first and last letters of each answer: Trina and Freda.

Two little girls near London dwell,

More naughty than I like to tell.

Upon the lawn the hoops are seen:

The balls are rolling on the green. TurF

The Thames is running deep and wide:

And boats are rowing on the tide. RiveR

In winter-time, all in a row,

The happy skaters come and go. IcE

“Papa!” they cry, “Do let us stay!”

He does not speak, but says they may. NoD

“There is a land,” he says, “my dear,

Which is too hot to skate, I fear.” AfricA

(“Two little girls near London dwell”)

But it was not solely children who inspired Carroll to his knottiest verses. Building on a system invented by Dr Richard Grey in 1730, Carroll worked out mnemonics for logarithms, the dates of kings or the specific gravities of metals and resolved that information into couplets by means of a code. The couplets are often as difficult to recall (at least for anyone but Carroll) as the information itself; or, rather, the relationship between a couplet like “Columbus sailed the world around / Until America was found” and the buried date 1492 can only be understood by learning the cipher system.5 These “Memoria Technica” crop up in unexpected places, often in the diaries and in letters, and I have offered a few of them only.

After the Alice books Carroll’s poetry takes a rather different turn, away from parody, into the darker The Hunting of the Snark (1876). Behind that poem lie travellers’ tales and exploration, including the loss of Franklin’s expedition in search of the Northwest Passage, which so preoccupied Victorian society in the 1850s, and Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, and even something of Frankenstein. The Hunting of the Snark came to Carroll first through its intact last line: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.” Quite what this means remains a mystery except that, as Alice says about “Jabberwocky”:

“Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas – only I don’t know exactly what they are! However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate—”

(Centenary Edition, 134)

At the end of the Snark that observation is reversed: something killed someone, it would seem. “For the Snark was a Boojum”: that italicised “was” suggests that the snark being a boojum confounds a host of unnameable possibilities. Late in his life Carroll insisted that he “didn’t mean anything but nonsense” in the poem, but he was intrigued by the readings that clustered around it, such as that it represented the search for happiness or for the absolute. In a letter to the Lowrie children he made a remark crucial to understanding how his creativity worked despite the precision with which he wrote and rhymed:

As to the meaning of the Snark? I’m very much afraid I didn’t mean anything but nonsense! Still, you know, words mean more than we mean to express when we use them; so a whole book ought to mean a great deal more than the writer meant. So, whatever good meanings are in the book, I am very happy to accept as the meaning of the book. The best that I’ve seen is by a lady … – that the whole book is an allegory on the search after happiness.

Elsewhere he is more succinct: “My dear May, In answer to your question ‘What did you mean the Snark was?’ will you tell your friend that I meant that the Snark was a Boojum. I trust that you and she will now feel quite satisfied and happy.”6

The Snark is unusual in being composed intact rather than clustered around shards of his own or other writers’ previous poems, as in his many parodic works. Here it seems to have spun backwards out of that single impenetrable line. As so often, Carroll was fortunate in his illustrator, and Henry Holiday well captured the bluntness and the obscurity of the poem.

Carroll’s Reading and His Parodies

Carroll read poetry of many kinds with delight. He kept abreast of a great deal of recent and contemporary poetry, as well as being deeply familiar with the English and Latin classics. He loved William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. He was much attracted by Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862) and came to know her well. In his personal Scrapbook now available online from the Library of Congress, he has pasted in two of her poems. He owned Adelaide Procter’s A Chaplet of Verses (1862) and her two-volume Legends and Lyrics (1858–61), possibly in the 1866 edition that included an illustration by John Tenniel, his inspired collaborator as the illustrator of both the Alice books. Carroll owned Swinburne’s highly controversial collection of poems Poems and Ballads (1866). He read William Morris’s The Defence of Guinevere, and Other Poems (1858) when it first came out, and he owned The Poetical Works of Edgar Allan Poe (1853). Of course he read Tennyson at large and owned at least twenty-six collections of his work, including the German translation of “In Memoriam”. But he also read now little-known writers such as William Motherwell, both his collection of ballads Minstrelsy Ancient and Modern (1827) and his Poetical Works (3rd edition, 1849) and Robert Pollok’s large epic The Course of Time (1829), which went through many editions and which, Charlie Lovett notes, “was issued in 1857 in an illustrated edition which included pictures by John Tenniel”.7 He read also the works of humorous poets like Bon Gaultier8 and Praed, and his copy of the two-volume The Poems of Winthrop Mackworth Praed (1864) was offered for sale in 1965. And every week he read Punch with its wealth of comic verses. Later in his life he greatly enjoyed Gilbert and Sullivan’s operettas with their witty verses and catchy tunes and their friendly satire on social mores. The list could be greatly expanded and those interested will find many other examples in Charlie Lovett’s excellent bibliography, Lewis Carroll Among His Books (2005).

Carroll was above all a superb parodist. Parody is a curious form, relying as it must at the outset on what it will overturn and perhaps obliterate. Many of the poems he parodies would have been well known at the time but are unknown to us now, the more so because his version has usurped their standing. An example is the poem by David Bates discussed below (“Speak Gently!”); another is Robert Southey’s didactic poem “The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them”, which lies behind “‘You are old, Father William’ ”. They were in authority then; his version is in authority now. Inevitably the loss of the original in our reading takes away a level of debate and of comedy. Sometimes their shadows do still haunt his poem; occasionally both versions still survive alongside each other, as “Twinkle, twinkle, little star” does beside “Twinkle, twinkle, little bat”. In the annotations I have tried to offer long-enough extracts from the originating poems to give their flavour.

Parody is a game rather than an accusation. Carroll’s parodies often show a certain affection or at the least a quizzical appreciation of the originals. He is amused by the moralising urgency of many of the verses and he eases the demands they make on children, or he encourages the child reader to vengeance without consequences. One of the most famous of th

e poems that turn “hoarse and strange” in Alice’s mouth is “How doth the little crocodile” – the first line ends in the Isaac Watts poem with “the little busy bee”, in Alice’s recollection it is “the little crocodile”. By keeping close to all the linguistic patterns of the Watts poem Carroll gives zest to his disruptive new version. Bee and crocodile both have appetites; the verses display each of them to the child reader: “How doth”. Both claim to improve things and make them shine; the Watts is on the left below, the Carroll on the right:

How doth the little busy bee How doth the little crocodile

Improve each shining hour; Improve his shining tail,

And gathers honey all the day And pour the waters of the Nile

From every opening flower. On every golden scale!

The glamorous crocodile allures the child, as had the gentler “opening flower” and honey; the first lines of both second verses share upbeat words: “skilfully” and “cheerfully”, “neat” and “neatly”. Then the still smiling crocodile shows his claws and relaxes, while the bee “labours hard”:

How skilfully she builds her cell! And labours hard to store it well

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland O Frabjous Day!

O Frabjous Day! Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense

Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (B&N)

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (B&N) Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (Barnes & Noble Cla

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (Barnes & Noble Cla The hunting of the Snark

The hunting of the Snark The Complete Alice in Wonderland (Wonderland Imprints Master Editions)

The Complete Alice in Wonderland (Wonderland Imprints Master Editions) Alice in Wonderland: The Vampire Slayer

Alice in Wonderland: The Vampire Slayer Phantasmagoria and Other Poems

Phantasmagoria and Other Poems Complete Works of Lewis Carroll

Complete Works of Lewis Carroll Alice's Adventures in Wonderland illustrated

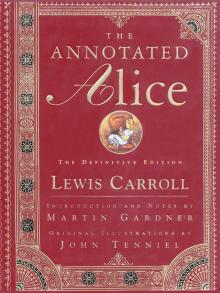

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland illustrated The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition (The Annotated Books) Through the Looking Glass

Through the Looking Glass The Annotated Alice

The Annotated Alice Alice in Zombieland

Alice in Zombieland