- Home

- Lewis Carroll

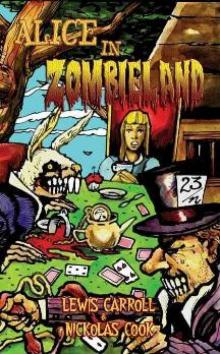

Alice in Zombieland Page 10

Alice in Zombieland Read online

Page 10

‘You ought to have finished,’ said the King. ‘When did you begin?’

The Hatter looked at the Dead Hare, who had followed him into the court, arm-in-arm with the Dormouse. ‘Fourteenth of March, I think it was,’ he said.

‘Fifteenth,’ said the Dead Hare.

‘Sixteenth,’ added the Dormouse.

‘Write that down,’ the King said to the jury, and the zombie jury moaned in unison and wrote down all three dates on their slates, and then added them up, and reduced the answer to shillings and pence. Bill the Lizard was too busy nibbling at his own dead fingers to write anymore. But since he seemed quiet and happy, no one seemed to mind enough to stop him from devouring himself instead of doing his duty as juror.

‘Take off your hat,’ the King said to the Hatter.

‘It isn’t mine,’ said the Hatter.

‘Stolen!’ the King exclaimed, turning to the jury, who instantly made a memorandum of the fact.

‘I keep them to sell,’ the Hatter added as an explanation; ‘I’ve none of my own. I’m a hatter.’

Here the Queen put on her spectacles, and began staring at the Hatter, who turned pale and fidgeted. She clutched the metal box close to her chest and sneered.

‘Give your evidence,’ said the King; ‘and don’t be nervous, or I’ll have you executed on the spot.’

This did not seem to encourage the witness at all: he kept shifting from one foot to the other, looking uneasily at the Queen and that metal box, and in his confusion he bit a large piece out of his teacup instead of the bread-and-butter.

Just at this moment Alice felt a very curious sensation, which puzzled her a good deal until she made out what it was: she was beginning to grow larger again, and she thought at first she would get up and leave the court; but on second thoughts she decided to remain where she was as long as there was room for her.

‘I wish you wouldn’t squeeze so.’ said the Dormouse, who was sitting next to her. ‘I can hardly breathe.’

‘I can’t help it,’ said Alice very meekly: ‘I’m growing.’

‘You’ve no right to grow here,’ said the Dormouse.

‘Don’t talk nonsense,’ said Alice more boldly: ‘you know you’re growing too.’

‘Yes, but I grow at a reasonable pace,’ said the Dormouse: ‘not in that ridiculous fashion.’ And he got up very sulkily and crossed over to the other side of the court.

All this time the Queen had never left off staring at the Hatter, and, just as the Dormouse crossed the court, she said to one of the officers of the court, ‘Bring me the list of the singers in the last concert!’ on which the wretched Hatter trembled so, that he shook both his shoes off.

‘Give your evidence,’ the King repeated angrily, ‘or I’ll have you executed, whether you’re nervous or not.’

‘I’m a poor man, your Majesty,’ the Hatter began, in a trembling voice, ‘—and I hadn’t begun my tea—not above a week or so—and what with the bread-and-butter getting so thin—and the twinkling of the tea—’

‘The twinkling of the what?’ said the King.

‘It began with the tea,’ the Hatter replied.

‘Of course twinkling begins with a T!’ said the King sharply. ‘Do you take me for a dunce? Go on!’

‘I’m a poor man,’ the Hatter went on, ‘and most things twinkled after that—only the Dead Hare said—’

‘I didn’t!’ the Dead Hare interrupted in a great hurry.

‘You did!’ said the Hatter.

‘I deny it!’ said the Dead Hare.

‘He denies it,’ said the King: ‘leave out that part.’

‘Well, at any rate, the Dormouse said—’ the Hatter went on, looking anxiously round to see if he would deny it too: but the Dormouse denied nothing, being fast asleep.

‘After that,’ continued the Hatter, ‘I cut some more bread-and-butter—’

‘But what did the Dormouse say?’ one of the jury asked.

‘That I can’t remember,’ said the Hatter.

‘You must remember,’ remarked the King, ‘or I’ll have you executed.’

The miserable Hatter dropped his teacup and half-eaten corpse hand, and went down on one knee. ‘I’m a poor man, your Majesty,’ he began.

‘You’re a very poor speaker,’ said the King.

Here one of the zombie guinea-pigs seemed to shake off some silent hypnosis, and despite the fact he wore one of those jeweled collars, the little rotting thing made a lunge at the dead hand which the Hatter held, and was immediately suppressed by the officers of the court. The soldiers piled on him, fighting to avoid his tiny snapping teeth. (As that is rather a hard word, I will just explain to you how it was done. They had a large canvas bag, which tied up at the mouth with strings: into this they slipped the guinea-pig, head first, and then sat upon it.)

Alice, for all her size, was still trying to figure out a way to get to that metal box. Her curiosity was becoming almost as powerful as her strange hunger now. She was glad for the sudden confusion and used it to edge closer to where the Queen was sitting.

‘If that’s all you know about it, you may stand down,’ continued the King.

‘I can’t go no lower,’ said the Hatter: ‘I’m on the floor, as it is.’

‘Then you may sit down,’ the King replied.

Here another undead guinea-pig gave a great shudder and made a grab for the Hatter’s corpse snack, and was suppressed in much the same way by the soldiers. Alice wondered why no one thought it strange that supposedly contrite creatures were suddenly turning violent—and in such a crowded place, too. It seemed to her someone would send out orders to clear the room if such things continued. But since there didn’t seem to be anymore guinea-pigs about, she thought: ‘Come, that finished the guinea-pigs! Now we shall get on better.’

‘I’d rather finish my tea,’ said the Hatter, with an anxious look at the Queen, who was reading the list of singers.

‘You may go,’ said the King, and the Hatter hurriedly left the court, without even waiting to put his shoes on.

‘—and just take his head off outside,’ the Queen added to one of the officers: but the Hatter was out of sight before the officer could get to the door.

Alice was getting close enough to the Queen that she could almost see what the metal box really was . . . just a few more feet.

‘Call the next witness!’ said the King.

The next witness was the Duchess’s cook. She carried the pepper-box in her hand, and Alice guessed who it was, even before she got into the court, by the way the people near the door began sneezing all at once.

‘Give your evidence,’ said the King.

‘Shan’t,’ said the cook.

The King looked anxiously at the Black Rat, who said in a low voice, ‘Your Majesty must cross-examine this witness.’

‘Well, if I must, I must,’ the King said, with a melancholy air, and, after folding his arms and frowning at the cook till his eyes were nearly out of sight, he said in a deep voice, ‘What are tarts made of?’

‘Pepper, mostly,’ said the cook.

‘Treacle,’ said a sleepy voice behind her.

‘Collar that Dormouse,’ the Queen shrieked out. ‘Behead that Dormouse! Turn that Dormouse out of court! Suppress him! Pinch him! Off with his whiskers!’

For some minutes the whole court was in confusion, getting the Dormouse turned out, and, by the time they had settled down again, the cook had disappeared.

‘Never mind!’ said the King, with an air of great relief. ‘Call the next witness.’ And he added in an undertone to the Queen, ‘Really, my dear, you must cross-examine the next witness. It quite makes my forehead ache!’

Alice watched the Black Rat as he fumbled over the list, feeling very curious to see what the next witness would be like, ‘—for they haven’t got much evidence yet,’ she said to herself. Imagine her surprise, when the Black Rat read out, at the top of his shrill little voice, the name ‘Alice!’

Chapter 12 Alice

’s Resurrection

‘Here!’ cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the zombies on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before. Some of the undead were making grabs for various members of the frightened and panicked audience. Alice could see one small bird subsumed by three of the zombie jurors and it disappeared in a shower of gore and feathers, with no time for even a squawk. Another zombie juror wrestled with a zombie lobster for a whiting, tearing the poor thing in half with their violent claws.

‘Oh, I beg your pardon!’ she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

‘The trial cannot proceed,’ said the King in a very grave voice, ‘until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,’ he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

The Queen hammered unseen buttons on her metal box and soon the zombies seemed to calm down and stop eating their fellow creatures. She brandished the stick, glowering down into the excited crowd. Her face was enough to quiet them.

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. To her great dismay, Bill’s tail snapped in half and went on wiggling at her feet. She soon got it out again, and put it right; ‘not that it signifies much,’ she said to herself; ‘I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.’

As soon as the zombie jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

‘What do you know about this business?’ the King said to Alice.

‘Nothing,’ said Alice.

‘Nothing whatever?’ persisted the King.

‘Nothing whatever,’ said Alice.

‘That’s very important,’ the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the Black Rat interrupted: ‘Unimportant, your Majesty means, of course,’ he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

‘Unimportant, of course, I meant,’ the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, ‘important—unimportant—unimportant—important—’ as if he were trying which word sounded best.

Some of the jury wrote it down ‘important,’ and some ‘unimportant.’ Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; ‘but it doesn’t matter a bit,’ she thought to herself.

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out ‘Silence!’ and read out from his book, ‘Rule Forty-two. All persons more than a mile high to leave the court.’

Everybody looked at Alice.

‘I’m not a mile high,’ said Alice.

‘You are,’ said the King.

‘Nearly two miles high,’ added the Queen, fingering her metal box, eyeing the zombies surrounding her. For the first time, Alice thought the older woman seemed to be a bit frightened by the sheer number of undead that surrounded her and the King. In any case, she clutched tightly at the box for protection. She hefted the killing stick, ready for a moment’s use.

‘Well, I shan’t go, at any rate,’ said Alice: ‘besides, that’s not a regular rule: you invented it just now.’

‘It’s the oldest rule in the book,’ said the King.

‘Then it ought to be Number One,’ said Alice.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. ‘Consider your verdict,’ he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

‘There’s more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,’ said the Black Rat, jumping up in a great hurry; ‘this paper has just been picked up.’

‘What’s in it?’ said the Queen.

‘I haven’t opened it yet,’ said the Black Rat, ‘but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.’

‘It must have been that,’ said the King, ‘unless it was written to nobody, which isn’t usual, you know.’

‘Who is it directed to?’ said one of the jurymen.

‘It isn’t directed at all,’ said the Black Rat; ‘in fact, there’s nothing written on the outside.’ He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added ‘It isn’t a letter, after all: it’s a set of verses.’

‘Are they in the prisoner’s handwriting?’ asked another of they jurymen.

‘No, they’re not,’ said the Black Rat, ‘and that’s the queerest thing about it.’

‘He must have imitated somebody else’s hand,’ said the King.

‘Please your Majesty,’ said the Knave, ‘I didn’t write it, and they can’t prove I did: there’s no name signed at the end.’

‘If you didn’t sign it,’ said the King, ‘that only makes the matter worse. You must have meant some mischief, or else you’d have signed your name like an honest man.’

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

‘That proves his guilt,’ said the Queen. She was so enraged and red-faced, she quite forgot all about the metal box and let it fall near her feet. Alice took note of it and edged a bit closer to her.

‘It proves nothing of the sort!’ said Alice. ‘Why, you don’t even know what they’re about!’

She could almost touch the box with her foot now.

‘Read them,’ said the King.

The Black Rat put on his spectacles. ‘Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?’ he asked.

‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, ‘and go on till you come to the end: then stop.’

These were the verses the Black Rat read:

They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.’

‘That’s the most important piece of evidence we’ve heard yet,’ said the King, rubbing his hands; ‘so now let the jury—’

‘If any one of them can explain it,’ said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid of interrupting him,) ‘I’ll give him sixpence. I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it.’ Her big toe was now covering the metal box; the Red Queen seemed to have forgotten all about it as she cowered a bit from Alice.

The zombie jury moaned as one and wrote down on their slates, ‘She doesn’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it,’ but none of them attempted to explain the paper.<

br />

‘If there’s no meaning in it,’ said the King, ‘that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. And yet I don’t know,’ he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; ‘I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. “—said I could not swim—” you can’t swim, can you?’ he added, turning to the Knave.

The Knave shook his head sadly. ‘Do I look like it?’ he said. (Which he certainly did not, being made entirely of cardboard.)

‘All right, so far,’ said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: ‘“We know it to be true—” that’s the jury, of course— “I gave her one, they gave him two—” why, that must be what he did with the meat pies, you know—’

‘But, it goes on “They all returned from him to you,”’ said Alice.

‘Why, there they are!’ said the King triumphantly, pointing to the meat pies on the table.

‘Nothing can be clearer than that.

Then again— “Before she had this fit—” you never had fits, my dear, I think?’ he said to the Queen.

‘Never!’ said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

‘Then the words don’t fit you,’ said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

‘It’s a pun!’ the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, ‘Let the jury consider their verdict,’ the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

‘No, no!’ said the Queen. ‘Sentence first—verdict afterwards.’

‘Stuff and nonsense!’ said Alice loudly. ‘The idea of having the sentence first!’

‘Hold your tongue!’ said the Queen, turning purple.

‘I won’t!’ said Alice.

‘Off with her head!’ the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland O Frabjous Day!

O Frabjous Day! Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense

Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (B&N)

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (B&N) Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (Barnes & Noble Cla

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (Barnes & Noble Cla The hunting of the Snark

The hunting of the Snark The Complete Alice in Wonderland (Wonderland Imprints Master Editions)

The Complete Alice in Wonderland (Wonderland Imprints Master Editions) Alice in Wonderland: The Vampire Slayer

Alice in Wonderland: The Vampire Slayer Phantasmagoria and Other Poems

Phantasmagoria and Other Poems Complete Works of Lewis Carroll

Complete Works of Lewis Carroll Alice's Adventures in Wonderland illustrated

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland illustrated The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition (The Annotated Books) Through the Looking Glass

Through the Looking Glass The Annotated Alice

The Annotated Alice Alice in Zombieland

Alice in Zombieland